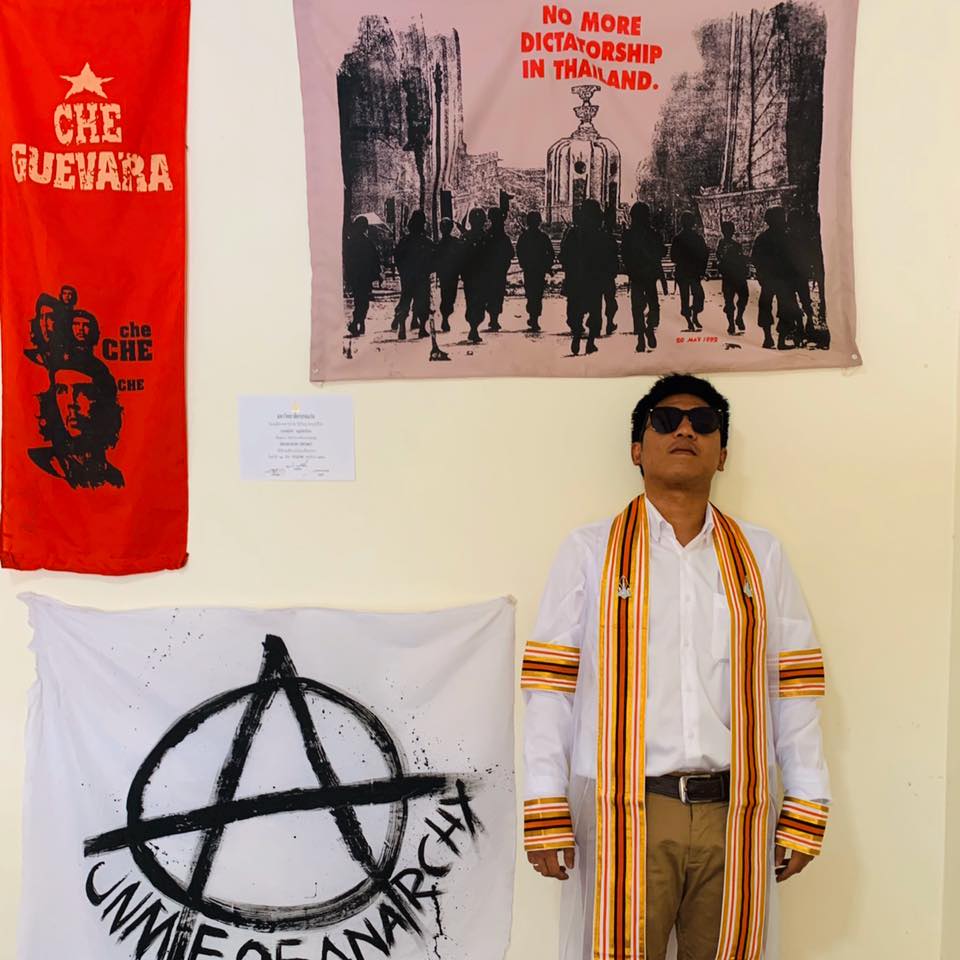

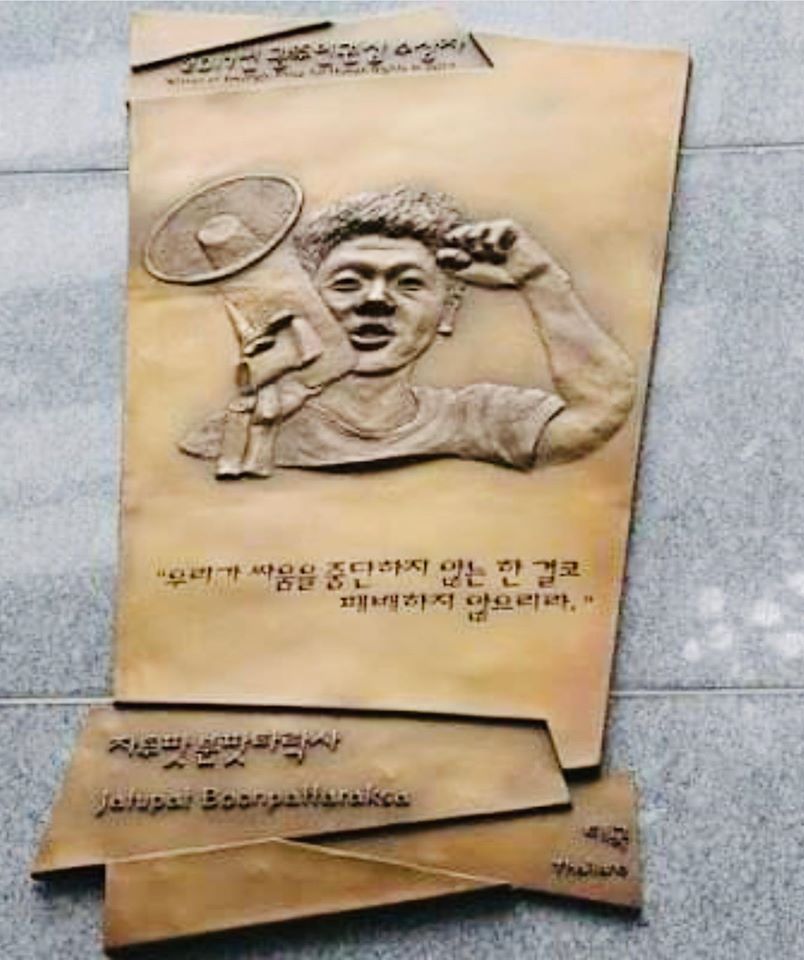

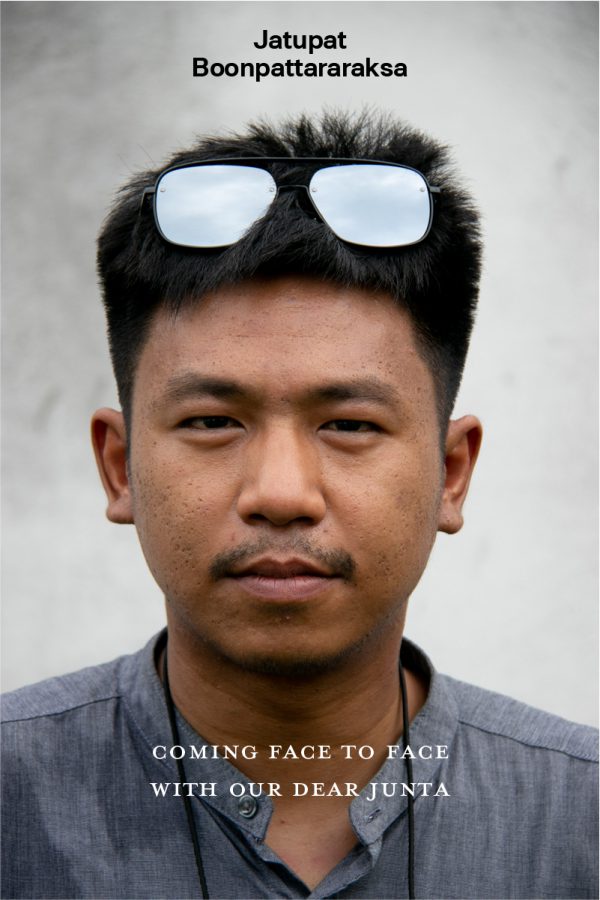

From a law student fighting for the rights of local communities with villagers in the Northeast; to coming out with a three-finger salute in front of General Prayuth Chan-ocha; to being a voice for Thai society in the first three years of the junta rule; to calling out the problems of the 2017 constitution and being charged with all kinds of cases; to being imprisoned for Article 112 [the lese majeste law], and while his freedom was being stolen, receiving the Gwangju Prize for Human Rights in South Korea, which he couldn’t attend (his parents had to fly over and accept it on behalf of their son); to receiving his law degree in jail; and then, when he was released, having the opportunity to join a commission in Parliament and to go back and look at the person who arrested him in the eye –– it’s the twisting turns of the life of Pai, or Jatupat Boonpattararaksa.

WAY spoke with him one day before the 6-year anniversary of the May 22, 2014 coup.

It’s been six years of darkness, still with us. We see it. Although the darkness dares not look us back in the eyes.

Tomorrow (May 22, 2020) are you planning to do anything?

Tomorrow will be 6 years, right? I don’t think I need to do anything; everyone knows, after all these past six years. It depends on whether they can continue to stand it. For me and my colleagues, despite all sorts of orders, including Article 44, we didn’t fear. Of course, there were more than a few who did fear because all the NCPO does is create fear. At that time it was only the aunties [women a generation older than himself] or the various members of our “fan club” who came out to offer us support, and they were also scared, but they [still] came to give us support. But after a while we also saw them become the accused. They were proud to come tell us that now they were charged.

I feel that people are now aware. The answers are now clear as to how life has been, how politics has been. It’s clear with regards to everything. We only wait for one answer: when will everyone come out and speak out together, at the same time. Looking back to the first period, my group of people couldn’t stand it anymore. We came out before the villagers and townspeople [were willing to come out]. But this time around maybe we will have to wait until everyone comes out together. We must wait and listen to other people’s voices as a whole. If you want to have me come out and speak out every year, it’s not right.

You must understand. Early on when I came out and spoke out, it was because there were no [other] people speaking out, there was no one doing [anything]. But today there are people speaking out and doing [things]. And so I don’t need to speak out. I will do something else. I feel that the speaking out and actions I used to do were not able to change things. And so I will do something else, but with the same purpose.

What is your life like these days? What are you doing?

I am on staff with the Faculty of Law at Khon Kaen University, and I’m Secretary of the Paliamentary Commission on Law, Justice, and Human Rights, and the other role as member of the Select Committee to Study and Solve the Problem of Infringement of Human Rights and Covert Harms to Citizens in affiliation with the Future Forward group.

What is the role of the Select Committee to Study and Solve the Problem of Infringement of Human Rights and Covert Harms to Citizens?

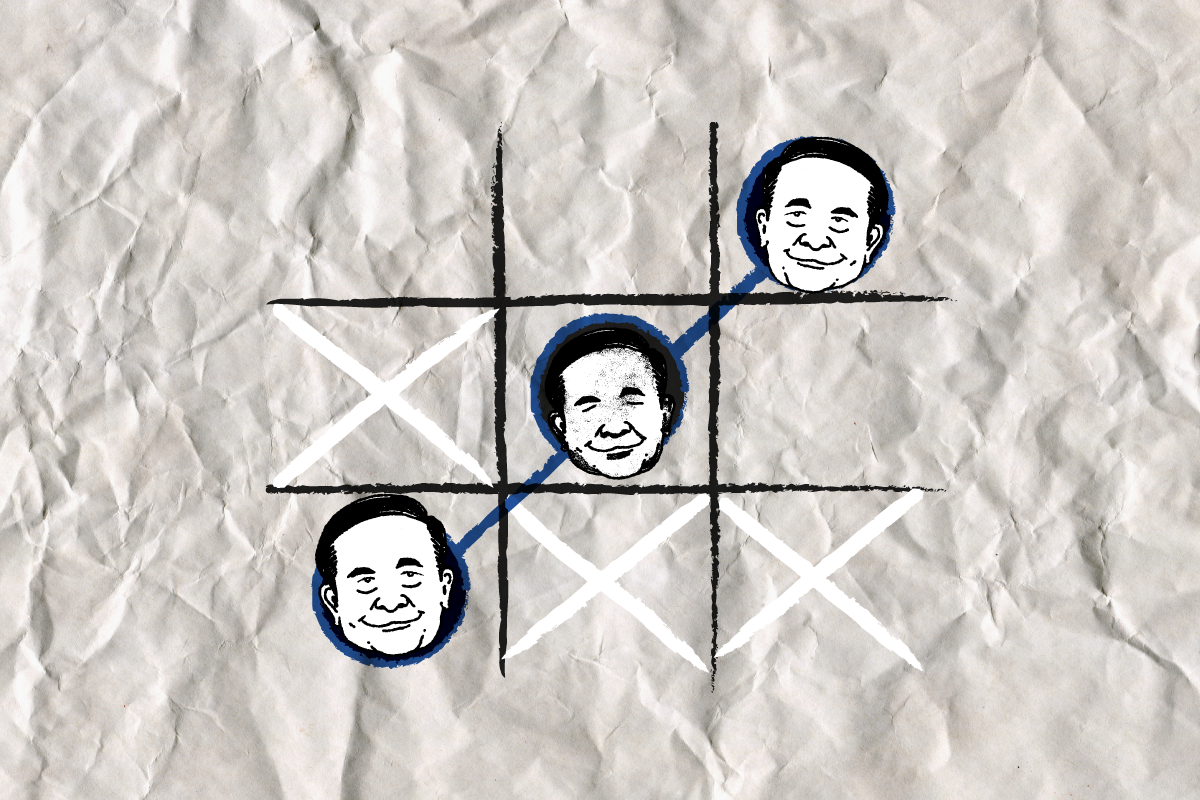

I have learned something in the participation. For some of my cases, I called in the soldiers or the persons who previously arrested me, who previously used the power of the NCPO and the power of the state, and questioned them. And so I was able to learn what they think. These people all had power in the period of the junta, right? But now that some time has passed, these people, must listen, must answer questions, even if this mechanism isn’t able to change anything. But some of their answers did clarify things for society, in some ways.

In this [parliamentary] committee, there will be an investigation into matters of the law. There will be the problems of the villagers, and all sorts of stories. We call on state agencies that are involved to come hear about the problems. We will hear from both the villagers and the state agencies. They were never all in a mechanism like this before and never had to listen to anything [like this] before.

In one instance, for example, we called Lt. Col. Phitakphon Chusri and Col. Burin Thongpraprai to ask them what discretion they used in their arrests of citizens during the NCPO era.

They all said they weren’t using discretion, they were just following orders. And these answers made us know that the use of power during that period didn’t involve any discretion at all. It was the use of orders with no interest in what was right or reasons. They couldn’t answer the questions at all. They just said “The boss ordered it.”

But at least we know now that the soldiers who took action in the area weren’t thinking for themselves, but they did what they did because of orders. They didn’t question whether these orders were right or lawful, but [just] followed the orders. And so it is a fact that we can affirm to society that the use of power in the NCPO era didn’t have reasons. It was nothing but the use of power.

How did it feel to be face to face with this person under conditions different than before?

It feels like I have restored my humanity. My presence was on a par with him. Before I would sit as a captive accused. He would be wearing a uniform. I would be wearing the outfit of a prisoner. But today we sit face to face across from each other and speak with reason, and I think this rescues my dignity. Even though we aren’t able to do anything in this situation, I feel OK. At least my dignity and humanity have been restored. I feel like that. To be able to sit in a normal way with this person who previously did things to me. It’s hard to explain.

What questions did you ask Lt. Col. Phitakphon?

I asked him about the use of power. But I can’t remember all the details. I asked, who was the person who locked me up? There were also many cases in Khon Kaen involving him [Lt. Col. Phitakphon]. I got to ask questions about each case in detail. With regard to my own cases, I asked who ordered I be locked up?

[And] did he have an answer?

He said, “The court.” He was trying to annoy me . . .

When you looked into his eyes, how did you feel?

He didn’t dare look me in the eye. Exercising your right of assembly is obviously not wrong. And this makes me feel that when truth is revealed and we must sit face to face, he’s embarrassed.

Looking at the basis for why they arrested all of us, it was nonsense––all of it. They could only say, “We were following orders.” As for whether they liked or didn’t like the order, there was no thought process. And so it’s like people who answer the questions like, “I didn’t think,” like, “I never thought about it before,” because they didn’t use their own thinking. If people think for themselves, they will answer naturally. They will have humanity, right? But the people we asked whatever of, could only answer, “I don’t know.” I asked questions regarding the orders, “So they weren’t right?” They couldn’t look me in the eye. The silent look in their eyes was fighting and resistant. Even though before this they had had power, they were dignified, great, tough and gruff, experts . . . now they were silent and didn’t dare meet my eyes.

When you became active in Parliament, in what way was it more complicated than the struggle during years 1-3 of the junta [rule]?

In the Parliament, the military dictatorship, as we could all clearly see, straightforwardly uses power of every type to the max. But as soon as it’s the mechanism of Parliament, there is the power of investigation. But it isn’t complete. It’s good that there is the mechanism of whatever [parliamentary] committees mentioned here. But they don’t have power. In the end the power is with them. Under this version of the constitution, the power is with Prayut, it’s with the Senate, and there is no way to change. It’s like a channel for release, but not a channel for solving the problem. With politics having deceptive mechanisms––it’s like “have for the sake of having it”–– the dictatorship has the majority vote in the end. And so I still use the word “dictatorship” same as before. The election was just a ceremony. But the atmosphere has improved. A good thing coming out of the election is the improved atmosphere. But they still use power through other mechanisms, for instance through the courts in abolishing Future Forward Party. They use the mechanism of Parliament with the majority vote, like with the no confidence debate or the re-voting.

If I look back to my life in the period I was a student, which was the era of the NCPO, half of the time of my study, I was in jail.

When I look back, I didn’t have lots of reasons for my struggle with the dictatorship. It was just that there was no one coming out to do it. And so I came out and asked questions. I asked, “Why must you overthrow the government? Why not have elections?” Because “the coup is not right.” And then the coup happened for real, the more the meaning of “it’s not right” became clear.

On top of everything else, I opposed them before May 22, 2016. I’d been speaking out since Suthep [Thaugsuban] came out. I was speaking out since all the way back in December 31, 2015. And before that point, people used to praise and admire the Dao Din group, am I right? Because [we] worked to help the villagers. But as soon as we came out speaking about politics, people shook their heads and ran away. Even though these were both [really] the same issue. We’d been saying for so long, “Coups wouldn’t fix problems.” So when a coup happened, we fought. And we fought until we couldn’t fight anymore. And so at the first anniversary of the coup, we came out in opposition again, raising the cases of [our] opposition to drilling for petroleum, land reclaiming for the potash mine, and privatization of the university system.

If there hadn’t been a coup, the drilling for petroleum in Isaan would have not succeeded. Today if you drive on Mitrapaap road out of Isaan going to Bangkok, you will see the petroleum pipe that has been laid down. And what does this mean? If there has been no coup, doing petroleum would not have succeeded. Because there would be resistance, struggle, the rights of villagers, the rights of the community according to the Constitution of 2007. That has disappeared. And why? Because this time around, it’s not just a political problem. It’s a coup for resources, overthrowing everything.

The Constitution of 2007, which used to have a mechanism for the villagers to oppose [a project], has been eliminated, has been revised. And the petroleum stock! We tried to pose the question, “Who gets the benefits?” Go look at the stock market. From here on, people will gradually know who. Am I right? Which means that the overthrowing of the government this time was completely horrible.

In the first year, therefore, I came out and spoke up. All the resources have been affected. The villagers in many places were driven off their land. Let me jog the memory on those stories so that you will see the despicable evil of the military dictatorship. My associates and I objected with reason. We spoke with reason. Therefore, on the first anniversary of coup, in 2015, we came out objecting to 7 issues, with seven people. We spoke about the matters just mentioned: petroleum, the land, privatization of universities. Together we fought, giving it all we had, but after the coup, all the different things started happening.

In 2016, we came out campaigning “Vote No” in the referendum on the 2017 Constitution, and were arrested again. I fought in every way. We lost but kept on fighting. We were disappointed in the results of the referendum. Some people sighed. Some people fought on. Because it was a testing of power. In the end, there was the problem in the Parliament that we all saw. In the end, the things we’d been saying since long ago all really happened.

This year it’s been 6 years that they are with us. How has the process of justice been twisted? Legislation, management, justice . . . Important principles in Thai society have been totally lost.

If you look at it from the legal perspective, this is how it looks. I’ve studied law. The first thing is we believe in respect for the law. But the coup d’etat doesn’t respect the law. Therefore we came out. But jurists in Thai society believe this is law. The courts also accept that the coup is the top state power. We raised the matter with the courts. The courts were unwilling to bring charges. And furthermore, the courts were the ones certifying power for the NCPO.

But in the end, it was confirmed the power of the NCPO was not real law. Did you see? The courts also dismissed the charges. So what is right? What is just? What is true? In one era, you would establish that “this is wrong” although it is not wrong. So what’s the universal norm? Or in one era, you will say that this thing is wrong, but coming to another era, you say it’s right. So it’s OK to act this way?! Are we under the rule of law or under a society in which dictators are respected? I don’t understand. All the affiliated elements [of the regime] follow along together. The courts also took part. Oh, they, the judges, are so well dressed. They passed the verdict and imprisonment actually ensued. It’s ridiculous to me. Then, how can one be surprised to see the generation of youths came out to protest?

Your generation raised the three-finger salute. Today’s youth raises their cell phones. Is the atmosphere of society different [between the two periods?]

The atmosphere isn’t different. But these days the number of allies has greatly increased. As for the atmosphere in those days, we also had people who didn’t agree [with what was going on]. There were people who came out for the movement, came out to fight. The aunties who were in our “fan club” advanced from being members of our fan club to being defendants in all kinds of lawsuits, which pile up continuously.

These days, people dissatisfied with the government have increased greatly. And they openly show themselves much more than in previous eras. In that era, there was still fear. It’s that back then the dictatorship’s power was complete across every format, while today it’s not across every format like before. There is no order 3/2558. There is no total power like that. It makes the ceiling on the freedom of society higher. The thing that the NCPO did well was to create fear. They used this fear to get results, but only in the era of NCPO. But for this era, after the elections, maybe I can’t use the word “democracy.” The atmosphere needs to improve a little. Because the rules of the election, which include the constitution, have problems. We need to address these matters, right? But one can say it’s “a transfer of power by means of an election.” Speaking this way is better. But the atmosphere is better than when we had the NCPO.

Right now society is pushing [back]. For example the abolishing of the Future Forward Party. The destroying of the votes of the young generation. I think there are many, many factors combined that make the people come out. And in the NCPO era, I also came out because of these factors. As you see in the scenario of the problems of society, the problems of truth. We see injustice. But at that time few people came out because of the fear. Now huge numbers of people come out because the atmosphere has improved. Additionally people have learned a lot over time. Because you have to admit that a portion of the people back then had hopes and expectations that the NCPO would come in and work and reform things for the better. But as time went by––one year, two years, three years––those hopes were lost, along with the economy, which is unbearable.

Right now students younger than me can see and can learn [the truth]. And so they come out and create a movement. And it’s a duty they must do. It’s the right thing to do. It’s something people must help each other do together. It’s so beautiful and gives me hope. I feel we still have the younger generation [who] have strength and fire, and are interested in society, justice, and what is right. I feel like it isn’t just me.

I want to tell you something. I have hope for the movement of young people. In our era, I feel that whatever events we organized, we’d only have about 10 or 20 people come. But this time around, it’s one or two thousand who come. I feel like I have hope based on the group of students who are on the frontlines in the struggle. Today there isn’t any political organization that is the leading organization. In the past, there was the Alliance, the Red Shirts, there was The United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship. After the junta arrived, which was when I came up, there was a movement of students, the New Democracy movement. But it was wounded. It was persecuted until now it is destroyed.

Right now what is happening again is a student movement, which tends to . . . have legitimacy. It’s a situation where everyone will be able to come together. Think about it a minute: If it was the Yellow Shirts coming out to protest, or if it were the PCAD (People’s Committee for Absolute Democracy with the King as Head of State), Red Shirts, or Future Forward Party coming out to protest . . . But if it is students coming out taking the lead, then we can also follow. In the past, we separated from the students. I am confused about that phenomenon, thinking “Hey! Damn it, how should we do this? Why is it students come out in such large numbers?” We’re confused about this phenomenon? Right? Right now, as soon as we’d established ourselves, along comes covid-19. I think that we and the students must not be separated. The students are the frontline, they are the leading organization that will be the foundation for the citizens, the people who are poor and suffering. They will be the people’s representatives.

I think that the Covid makes it all the more clear. We must look out from this crisis, right? In this crisis, what does the government treat as most important? It’s clear that they consider capital most important, not people. People realize this. The Covid situation makes it even more clear that people have no food, are out of work. The government is really terrible. They don’t have any other perspectives. They only exercise power. They’ve got nothing.

In the news people don’t come out over politics; but they are hungry, they can’t endure the situation and must demand something. More of this will happen. We’ll know more about this government – what they care for, the people or anything else. Their actions will tell. We all realize what has been going on very well.

Looking back to the day that you raised the three fingers in Khon Kaen six years ago, what all have you lost?

So much. So much has been lost since I came out. My privacy. My life also disappeared. I like to consider that they say, “In fighting for rights and freedoms of others, the first thing that disappears is the rights and freedoms of oneself.” I finally understand these words. Truthfully, I’ll admit, if I knew I’d go to jail for doing something like this, I might not have done it. I don’t think I should go to jail for these tiny matters. I didn’t feel it was wrong! At this moment I still don’t feel it was wrong. But from that day my life changed. After I took the exams––and I had to take the exams after other students, because on that day I was arrested and taken for an attitude adjustment––ever since that day, ever since that first step, my life has changed. Because on that day, the exams was scheduled in the afternoon. So I guessed we’ll go raising the three fingers in the morning, and in the afternoon taking the exams and then just take it easy . . . something like that. I thought it was that simple. But when we raised the three fingers, we were suddenly busted.

But it’s like the title of a book: “All They Could Do to Us” [by Porntip Mankong]. Yeah, like that. They can’t harm us any more than this. Maybe I’m a little lonely. A little depressed in some parts of my life. In the period of two years, I understand my life much better. It means that I have seen people in society from the very worst, from in prison on up to [those] I see in Parliament. I see high-class people driving fancy cars, stepping out to be greeted and protected by security guards. I’ve seen everything now. But I’m still the same person as before. But I have experience and many more lessons than before. My past keeps getting longer and there are more and more stories.

I heard that the period before you agreed to confess to the lese majeste case was a really difficult time.

It was horrible. I had to admit to something which I thought I wasn’t wrong. I had to fight with myself so much. I must say, I prepared for 8 months to fight, during which I was always hopeful that I would be freed on bail. I had been studying law, and so I saw that there were opportunities for a bail. I had been studying law, and so I saw that there were opportunities for getting bail. The law opened up various channels. I didn’t know that it wouldn’t be like the law I had learned and been taught. (*laughs*) When at last I had to confess, I felt I’d lost myself. I couldn’t be myself. I had to be someone, I don’t know who, who was going to plead guilty. Right then, it wasn’t me anymore. I don’t know who it was. But it had to be done. Because there was no choice. This was the best way. There was no point in speaking of justice or what was right. It was the best choice at the time.

But having the chance to come face to face with these people, and they wouldn’t dare look you in the eye, did that help restore anything back to you?

I feel it’s not too late to pursue justice. I didn’t want this to be the aim of my life. But I also can’t forget the things he did. But I also don’t want it to happen again. When I found out that Niranam (Anonymous [on Twitter]) was also charged [with lese majeste], I was so sorry for him. What? This is still happening?! I understood that I was the last person. Then when I saw that Niranam had been charged, [I was like] “Was it ever gonna end?” But I’m not dead yet. Until the day I meet justice, I’m going to think like this.

Life can be better than this. You must believe it. Other countries can do it. Why can’t we? Other countries can [just] be democracies. Why do we have to be a “Thai-style democracy”?

We can be democratic according to the universal standard––a good life, universal human rights, good welfare is possible. We must be brave to cross over . . . to overcome whatever. It isn’t only about giving us this little bit of money. It’s that if you go look at other governments that care more about their citizens: all kinds of welfare, the giving out of various things. Now look at ours. They can’t even give us 5,000 baht ($158 dollars) [promised payment for the covid-19 crisis]. They don’t see, they disrespect the citizens! Even though they are living difficult lives. They are impoverished! There is no chance they will understand because they were born full and comfortable. There is no chance they will understand when just being able to eat is one kind of happiness, one kind of life. There is no chance they will understand. They never live with people like this. They never connect with them. There is no chance they will understand. There is only all of us who understand each other. The class that rules has never understood us. And they never do anything good such that my life improves. They only do things to improve their own lives.

We have to accomplish this by ourselves. Please just one time! It’s time to come out, just one time. Come out together. Come change the society to whatever you damn well want. I believe Thai society has lots of problems: education, military conscription, LGBT matters. Oh! . . . so many, many things. It’s just that we don’t come out strongly at the same time. I want [us] to be like, “[OMG], it’s been SIX years already!”

First Published in Thai

สบตากันหน่อยเถอะว้า รัฐประหารที่รัก: จตุภัทร์ บุญภัทรรักษา

Translate by Ann Norman