Introduction: The Khon Kaen Model and Light Rail Transit

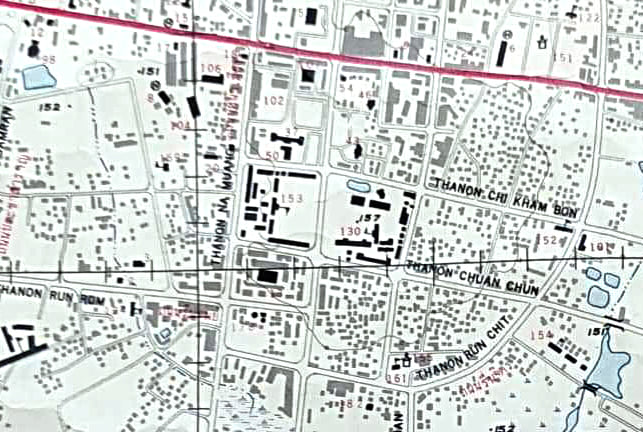

For several months towards the end of 2018 roadside LED screens at traffic intersections in the provincial Northeastern Thai city of Khon Kaen were looping promotional videos made for the city’s development corporation. The videos presented a computer-generated, colour-saturated landscape, scarcely recognisable as Khon Kaen, enhanced by twenty-first century public transit. Drivers held by a red light on traffic-choked Mitraphap Road could glance up at the glitching screen and see smooth 3-D renderings of trams gliding serenely on a palm tree-lined track through a pristine, idealised cityscape, zipping between stations of brilliant white, unweathered concrete. Distracted, earth-bound drivers were momentarily offered an extraordinary vantage point, a restlessly kinetic, aerial view, swooping and circling dramatically around the little trams as they cut urgently across a cityscape that both was, and was not, the one they were driving through [Fig. 1].

The CGI videos were promoting plans to build a 26-kilometre light rail network along the route of the main highway bisecting the city, a flagship project of the Khon Kaen City Development Corporation, also known as the Khon Kaen Think Tank (KKTT). KKTT was established in 2015 by a group of twenty of the city’s prominent business figures, each of whom contributed an initial investment to the corporation, for the purpose of developing the city’s infrastructure and promoting economic growth. The businessmen of KKTT had shaken up the province’s public transport plans. A decade earlier a research centre at the local university had made a case for dealing with the growing traffic problems in the urban areas of the province by creating a low-cost bus rapid transit system, a fleet of buses running on dedicated bus lanes. This was quietly shelved by KKTT in favour of the more spectacular, more ambitious and more costly light rail transit system. Whereas the bus network plans were designed to address a growing traffic and environmental problem by promoting a shift from private cars to public transport, the light rail network was one element of a more ambitious plan for urban growth which would capitalise, according to its promoters, the development corporation, on Khon Kaen city’s key assets, its location on the Mekong region’s strategically important transport routes: the high-speed rail line linking Kunming in Southern China to Singapore and the integrated transport infrastructures of ASEAN’s Economic Corridors. Buses may have been part of a solution to a growing congestion problem but light rail, or more specifically the 18 or so stations that would be constructed along the route and the land around them, now packaged as sites for potential development, were better raw materials from which to conjure the future growth possibilities of the city.

As Anna Tsing observes speculative enterprise involves dramatic projection, conjuring. “Profit must be imagined before it can be extracted”, she writes (2005, p. 57). Mining companies must dramatise their modest finds as a foretaste of the riches lying beneath the ground. Start-ups must “dramatise their dreams in order to attract the capital they need to operate and expand” (Tsing 2005, p. 57). Frontier-making in the city also hinges on dreams: the dream of vast untapped demand for the city’s land and real estate. The promise of new transport infrastructure bringing unprecedented flows of people from across the region nourishes such dreams, justifying the expansion of private medical centres and hospitals, the construction of convention centres, condominiums and retail outlets. These in turn, and the revenues they promise, make the extravagant cost of building the light rail network appear not only viable but necessary.

Pushing ahead with their plans KKTT established a public-private partnership with the five Khon Kaen municipalities linked by the proposed LRT network, the Khon Kaen Transit System (KKTS). Meanwhile, they lobbied the Minister of the Interior whose approval they needed for the devolution of responsibility for building and operating the public transit system. According to one KKTT figure scepticism turned to support when the minister grasped that Khon Kaen’s LRT would not require any public financing from central government. In fact, the plan to build a transit network primarily through private investment and run it through a private-public partnership was heralded as a model for other provinces to follow. Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha cited the project as an example of the ruling Junta’s policy of Pracharat,state and civil society collaboration, fiscal autonomy and collective action responsive to local needs. In a video address posted on the KKTT YouTube channel on 24th November 2017 the PM stated, “in line with the government’s strategies and… in tune with the needs of the people of Khon Kaen province, who have also participated in their development, without having to depend on the central budget as the only source of income”.

An almost identical narrative was being articulated by individuals linked to the Khon Kaen development corporation. On the day in which the project cleared its final obstacle, securing approval from the Land Traffic Management Commission of the Ministry of Transport, KKTT founder Suradech Taweesaengsakulthai gave an interview for the local news site E-san Biz in which he stated, “this is the first time in Thailand that locals (ท้องถิ่น) will get to create a large-scale mass transit system for ourselves with our own funding (Suradech 2018)”. This was emphatically not, he went on, merely a question of building a rail system. The way the system would be financed and managed would break new ground, as a model in which public infrastructure is built exclusively by private capital. Suradech stated: “The Skytrains that we see in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area, the Skytrains that are about to appear in the provinces, those Skytrains use tax money from the Thai people. With our Khon Kaen model, this Skytrain does not use subsidy money from the government.” Suradech positioned the Khon Kaen Model as a contribution to meeting long-term national goals: it brings innovation, it is about “changing the way we do things” in order to move beyond Thailand’s middle-income trap. There has been widespread praise for the Khon Kaen Model, it is viewed by government and media alike as an exemplar of private sector-led innovation, fiscal restraint and local self-determination. What follows is a cooler appraisal. My purpose is to clarify the dynamics of urban development that the localising agenda behind the Khon Kaen Model obscures in the hope of opening up a discussion of alternative development pathways that are currently foreclosed.

Localism, region and city in Northeast Thailand

The LRT and the Khon Kaen Model constitutes a localist inflection to agendas best described as entrepreneurial urbanism which are increasingly prevalent in the cities of Isaan. In the urbanised areas of the Northeast, the promise of new cross-border connections are promoting fresh rounds of speculative investment. In Khon Kaen as in other cities in Thailand, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, an efflorescence of urban development buzzwords and growth formulas, from the creative city to the smart city to the liveable and sustainable cities, to Transit-Oriented Development or TOD, and the ‘railway-innopolis’, is indicative of an intensely entrepreneurial character to urban governance. In Harvey’s seminal account entrepreneurial urbanism is characterised by urban governance whose principle goal is: “to lure highly mobile and flexible production, financial and consumption flows into its space” (1989, p. 11). The Darwinian churn of urban development concepts and trends largely reflects the speculative nature of urban investments: “the inability to predict exactly which package will succeed and which will not, in a world of considerable economic instability and volatility” (Harvey 1989, p. 11). A form of localism – a positive orientation towards local action – is implicit in this kind of entrepreneurial urbanism, insofar as it describes action undertaken to “maximise the attractiveness of the local site as a lure for capitalist development” within a historical conjuncture of intensifying inter-urban competition (Harvey 1989, p. 5). In Harvey’s account an older tradition of civic boosterism, typically driven by the coalition of local capitalists whose mouthpiece is the local chamber of commerce, is given a reboot in the entrepreneurial turn. Newly formed public-private partnerships come into the ascendance as the principal agents driving the construction of an urban image and the re-organisation of urban space. As such, urban entrepreneurialism, in Harvey’s (1989, p. 14) words, “meshes with a search for local identity and, as such, opens up a range of mechanisms for social control”, in which an ideology of locality, place and community become central to urban governance. What is needed is a critical perspective on this ‘meshing’ of entrepreneurialism and localism, the idealisation of the local in the rhetoric of urban governance.

The perspective developed here is informed by Mark Purcell’s concept of the local trap, essentially an invitation to always question the virtue of decentralisation and the local scale. Purcell writes, “The local trap equates the local with ‘the good’. It is preferred presumptively over non-local scales” (2006, p. 1924). Local collective action and decision making is assumed to be participatory, empowering citizens and enhancing democracy. Localisation is seen as the privileged path to the realisation of socially just outcomes. Yet, as Purcell observes, proponents of entrepreneurial or neoliberal urbanism, characterised by the retreat of the state and the capture of public services and infrastructure by private interests are often also enthusiastic advocates of decentralisation and local ‘self-reliance’. Rather than seeing the local scale as a repository of unchanging properties and values, Purcell urges us to investigate which actors and agendas are empowered by a strategy of localisation, the point being that “it is actors and agendas that produce outcomes, not the scales through which agendas were realised” (Purcell 2006, p. 1929). Scale making as strategy, involving the reconfiguration of relations between scales (e.g. local and national), becomes the object of inquiry, with an acceptance that “localisation should raise no a priori assumptions: it points to an ongoing struggle among competing interests” (Purcell 2006, p. 1929).

At its simplest localism can be defined as “a positive disposition towards the decentralisation of political power” (Clarke & Cochrane 2013, p. 10). But the simplicity of this definition conceals within it a host of contradictions and ambiguities. For example, Clarke and Cochrane, writing about localism in contemporary British politics, draw attention to the two distinct philosophical traditions informing a positive commitment to decentralisation in that context: a classical liberal belief that local government is more efficient, less bureaucratic and more responsive to local needs, and a communitarian belief in local communities as agents of responsible collective action. They argue:

When localism is used in political discourse, its meaning is often purposefully vague and imprecise. It brings geographical understandings about scale and place together with sets of political understandings about decentralisation, participation, and com- munity, and managerialist understandings about efficiency and forms of market delivery, moving easily between each of them, even when their fit is uncertain.

Clarke & Cochrane 2013, p. 11

It is precisely the slipperiness of the concept of localism, its ability to bear contrary political values and projects that makes it attractive. Clarke and Cochrane make a case for a methodology that tracks the ways in which localism is mobilised: ‘the rationalities, mentalities, programmes and technologies’ of localism.

In the Thai context localism has historically been regarded as a profoundly anti-urban orientation, a moral discourse centred on the virtues of the self-sufficient rural village and its community. As Hewison argues, a localist conception of the rural village as a model of self-reliance and community empowerment rooted in NGO-activism was resurrected in the aftermath of the 1997 economic crisis (2002, pp. 148-149). It was also at this point that King Bhumibol began to propound his ‘philosophy’ of rural self-sufficiency during his annual televised birthday speeches. As an alternative to crisis-prone capitalist development and the instabilities of globalisation, rural localism attracted both conservative and radical supporters (Hewison 2002, pp. 148-149). A sharply drawn rural-urban dichotomy was a central feature of this localist discourse. The values of the rural community, including solidarity, mutual support, care for the environment, are constructed in opposition to the prevailing orientation of urban life: money, consumerism, trade, commerce. According to the localist critique the growth of Thailand’s cities, and a focus on urban enterprise in state-development has come at the expense of rural communities and their values, whose status and health now needs to be restored. If the rural localism of the 1990s deployed a rural-urban dichotomy, the urban localism manifested by proponents of the Khon Kaen model seeks to tap into and rearticulate a deep-rooted regionalism in relation to the primacy of Bangkok, the seat of economic, political and symbolic power.

Throughout the twentieth century the urban centres of the Northeast have been shaped by major infrastructure projects designed to promote the territorial integration of the Siamese/Thai state. The construction of a railway line connecting Bangkok and Northeastern provinces in the 1930s enhanced the presence of the Siamese state and its agents of law and order in the peripheral areas of the nation. But it also brought new waves of settlers, notably Chinese migrants, to urban areas of the Northeast, contributing substantially to the growth of the region’s cities and commercial centres (Skinner 1957, pp. 198-202).

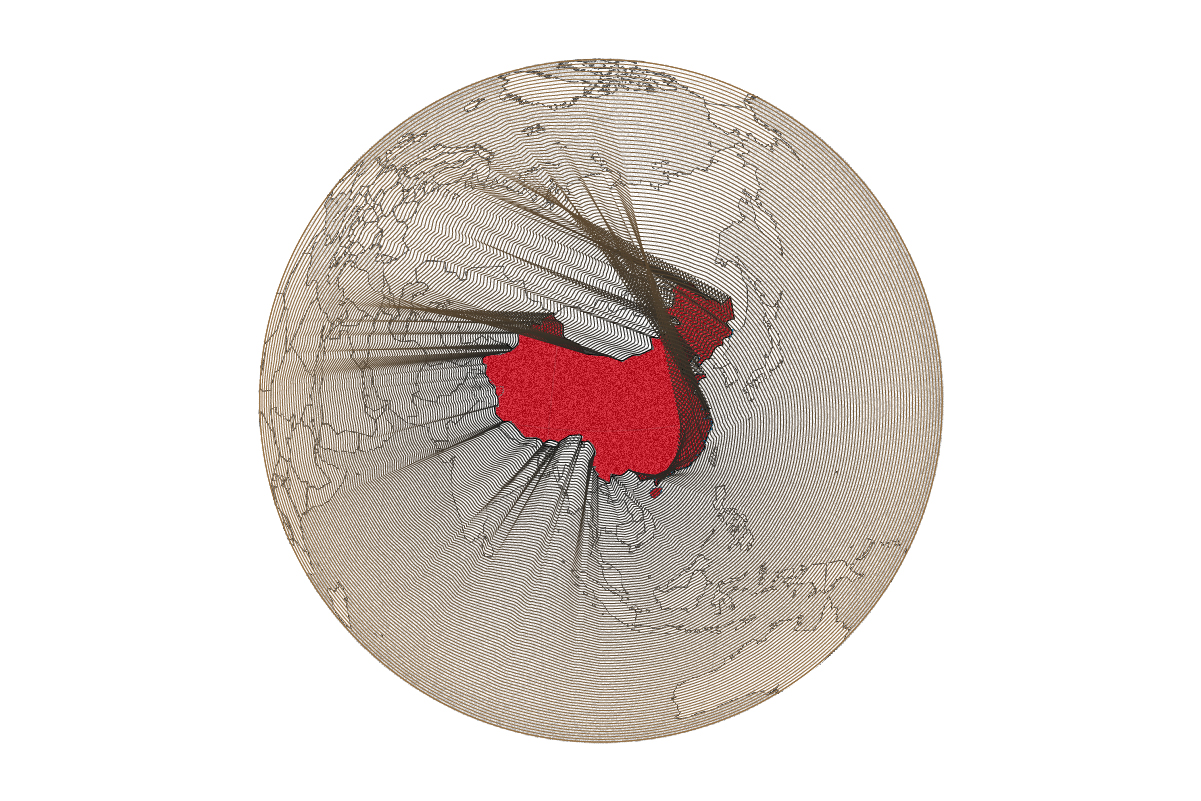

In the 1960s, under the paternalistic dictatorship of Field Marshal Sarit, regional economic development acquired a new focus. Sarit’s concern with the welfare of underdeveloped rural regions of the nation hinged on building new roads and improving water supply. Paternalistic commitment to development as a form of benevolent administration and the basis for political stability was a one key hallmark of the Sarit regime, the other being the ruthlessness with which it sought to eliminate dissent and opposition (Thak 2007). Bordering Laos, the Northeast became a key target of US-backed aid assistance designed to suppress communist insurgency and facilitate the presence of the US military. The construction of the Friendship Highway with US aid, linking the capital Bangkok and Nong Khai on the Laos border and passing through Khon Kaen and Udon Thani, site of a large US air base, contributed significantly to urbanisation in the northeast region. In the twenty-first century when US influence in the region has long-since waned it is China’s high-speed rail diplomacy that is shaping urban development in Khon Kaen, enhancing the city’s proximity to cities to its north in Laos and Southern China as much as Bangkok to the South. The guiding imperative behind this wave of infrastructure development is Chinese access to markets: transnational connectivity and cross border trade within the cities of the Greater Mekong region, rather than the territorial integrity of the Thai state.

The prospect of new infrastructures of connectivity that will enhance the cross-border links between the cities of the greater Mekong has galvanised the entrepreneurial urbanists of Khon Kaen who smell an opportunity. A fundamental obstacle however remains: the highly centralised character of the Thai state which substantially limits the scope of local authorities to engage in speculative place-making projects designed to lure flows of capital. The 1997 constitution brought momentum to a process of decentralisation in Thai local government (McCargo 2002). Reforms were introduced which, in principle at least, modestly extended the autonomy of elected local authority organisations (including city municipalities), which had been historically contained by the direct and indirect control of the provincial administration appointed by and accountable to the Ministry of Interior. Significantly, fiscal decentralisation was mandated in the Decentralisation Act of 1999 which introduced mandatory targets for the proportion of government revenue to be allocated to local authorities (Nagai et al 2008, pp. 1-3). However, the Act was subsequently amended, the targets revised dramatically downwards (from 35% in 2006 to 25% in 2007) and made non-binding (Nagai et al 2008, p. 11). In the current fiscal year, 2019, the proportion of government revenue directly under the control of local government is estimated to be 18-19 per cent, lower than the target figure nearly two decades ago in 2001 (Wyas 2020). The long-term reversal of the modest fiscal decentralisation of the early 2000s has been felt especially keenly by city municipalities to whom a range of government services have been devolved. Authoritarian centralisation has been further consolidated by the suspension of elections to all local authority bodies by the military rulers, the NCPO, in 2014. Despite a return of national-level elections in early 2019, local-level elections would not be announced until late 2020. Meanwhile, the long-term direction of national economic policy has promoted the formation of private-public partnerships and encouraged their role in delivering infrastructure projects (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board, 2017: 247). These dynamics of limited fiscal decentralisation thwarted by authoritarian centralisation, coupled with a policy environment favourable to public-private partnerships provide the context in which the Khon Kaen Model has emerged, in part in response to the stimulus of China’s infrastructural power.

The Two Khon Kaen Models

Promotional CGI videos construct a speculative image of future Khon Kaen, they are technologies of frontier making in which dreamlike visions are conjured. Photo images, of the kind that populate the development corporation’s social media feed, on the other hand, construct an image of the city’s governance in the here and now. Relationships are consolidated through the production and circulation of these images. Scrolling through the Facebook page of the Khon Kaen Think Tank one is struck by the frequency with which the group of suited leading businessmen are pictured with the Khon Kaen Mayor in formal pose flanking an esteemed visitor to the city, a delegation from Japan, a senior representative of the military regime in Bangkok (See fig. 2). When the Deputy PM Prajin Juntong concluded his opening address at a smart city forum organised by the Khon Kaen provincial administration, the men of KKTT, as if answering a silent, unseen call, assumed their places either side of him at the podium for formal pictures subsequently shared on the Facebook page. The pose becomes an image, an iconic sign of recognition, endorsement from the centre.

The Khon Kaen Model is a localisation strategy welcomed by the military regime and its civilian successor. The localism of the urban entrepreneurs does not rail against a profoundly rigged tax system which systematically facilitates tax evasion by the rich and fails to allocate adequate resources for public goods (Ananapibut 2017, 164). On the contrary, the urban entrepreneurs appear confident that the public shares their belief that private investment is morally superior to public spending. The localism of the entrepreneurs does not criticise striking regional income disparities. Income inequality within the Northeast is roughly on a par with national levels. It does not speak of the centre’s exploitation of the resources of the periphery or the suspension of local democratic processes. Instead it speaks of the need to rectify the province’s ‘over-dependency’ on the centre. The Khon Kaen Model makers present themselves as innovators and problem solvers, providing a solution to a problem identified and framed by national economic policy, the country’s middle-income trap. Far from leading a revolt against the centre they eagerly await the day when the Prime Minister will symbolically endorse their efforts by laying the first rail of their new tram network.

As Peera observes, public life in Thailand is crowded with models. There are models relating to poverty reduction, smog alleviation, marriage equality and so on, all of which use the English loan word (Peera, 2019). For Peera, the ubiquity of models betrays a ‘tendency to prescriptivism’ in Thai society. But the model is also a technocrat’s favoured vision of social change, a view of change from which all contingency has been purged and in which social movements are absent. In that respect models are a perfect counterpart to the notion of versions through which national strategy is articulated, as in Thailand 4.0. The prescriptive model and the metaphor of versions are both intended to provide a sense of technocratic authority guiding a process of incremental change, bringing order to disorder. When the model is identified with a place, when it is place-identified or place-branded, then it carries a desire for visibility and influence, the model is itself a bid for competitive advantage, it seeks to attract attention in a context of inter-urban competition.

As Peera details when the term Khon Kaen Model first appeared it had a very different referent. In 2014, Thai media reported on an alleged terrorist plot by a group of Red Shirt activists, 22 of whom were arrested at a hotel in Khon Kaen province and held in military jail. The Bangkok Post reported the Deputy Commander of the Second Army Region, Major-General Thawat Sukplang’s allegation that the ‘model’ was to be used across a number of Isan provinces to ‘create havoc’. In the junta’s use of the term Khon Kaen becomes a place (once again) where violence, disorder and rebellion are fomented, and with this usage a different logic of visibility is in play. The arrest is, as Peera notes, a media spectacle, momentarily capturing volatile flows of media attention. Images of the alleged terrorists’ arsenal are splashed across screens and pages, a fleeting distraction, a reminder of the vengeful, violent social disorder the military regime rescued the nation from. The second appearance of the Khon Kaen Model would seem to be an attempt to overwrite its predecessor, to associate Khon Kaen with private-sector innovation rather than plots of insurrection. Jailed without trial the lives of the alleged plotters, members of a proscribed political organisation, are held in permanent suspension whilst their successors, the entrepreneurs of the Khon Kaen Model mark 2, are endorsed by the military regime.

Briefly, the two Khon Kaen Models appeared to come into oblique alignment when KKTT co-founder and informal spokesperson conjured up an image of barely contained explosive force: ‘the balloon is close to bursting’. The ‘major stakeholders’ in Khon Kaen, Suradech implied, deserved credit because: “We didn’t poke at the balloon, so it would explode. We are the ones who untied the rubber band at the mouth of the balloon to let the air out” (Suradech 2018). Letting the air out suggests gently defusing local demands for social justice that might otherwise be channelled into political activism.

The Business Elite as Citizen Vanguard

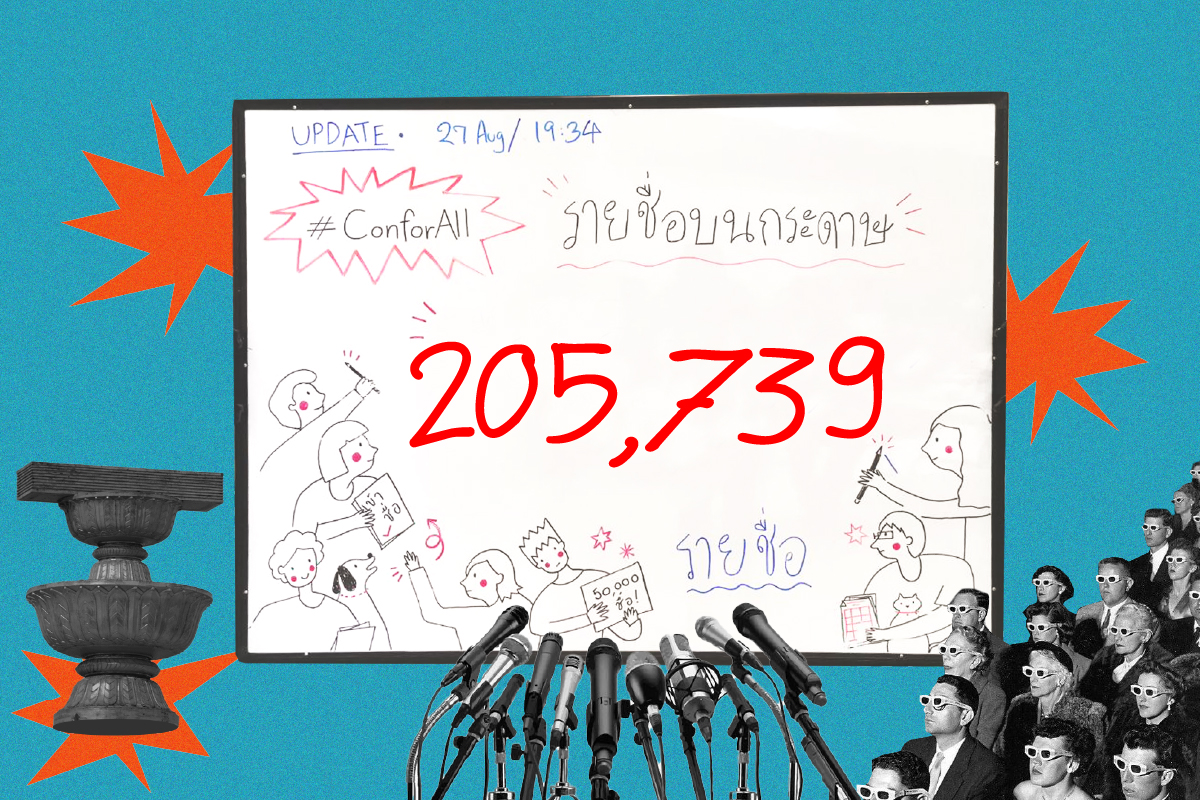

The urban localism of the development corporation cultivates the impression that local control equates with broad popular participation and support. In this they are aided and abetted by journalist commentators who, having fallen headlong for the local trap, are prepared to celebrate localisation as an end in itself. There is a common tendency to consider political agency in simplistic binary terms: it is either exercised by the state or by citizens: there is state power or people power. A perfect expression of this binary thinking is found in the juxtaposition of this Bangkok Post headline: “Citizens taking the initiative in Khon Kaen”, with the sub-heading underneath it: “A think tank formed by local entrepreneurs has propelled smart city plans for the Northeastern province” (Theparat 2017). It is true, the businessmen of KKTT are citizens, but not all citizens are business owners, and not all business owners are part of the small group of individuals that formed the development corporation and the private-public partnership, KKTS. The headline, however, gives the impression of a much broader collectivity, spontaneously engaged in driving forward the city’s smart city plans. Indeed, a deep reservoir of popular support is typically claimed by Khon Kaen’s entrepreneurial urbanists.

The Bangkok-based urban lifestyle magazine, A Day has provided a number of positive features on Khon Kaen, casting it as a forward-looking, agenda-setting city. The magazine’s in-depth feature on the Khon Kaen Model promised a look behind the headlines surrounding Khon Kaen’s light railway (Thanomkitti 2018). Like the Bangkok Post headline, it starts out by giving an impression of spontaneous popular will primed for local collective action. Citing the difficulties facing provincial urban development it states: “a lot of people in [provinces far from the capital] have given up on seeing their cities go forward…But not the people of Khon Kaen (Thanomkitti 2018),” Adding a few sentences later that “the residents of Khon Kaen” are not the kind of people who simply accept lack of central government investment. In a way that echoes the Bangkok Post’s headlines, the article posits a hinterland of local popular will out of which the private sector driven initiative of the Khon Kaen Model emerges. Displaying a circular logic, it then states that KKTT have been successful at inspiring “many people to see the importance of Khon Kaen development (Thanomkitti 2018).” The creators of the Khon Kaen Model, we are assured, would tell us that “city power comes from the power of the people (Thanomkitti 2018)”.

The media discourse on the Khon Kaen Model takes the form of what might be called entrepreneurial populism, a variation on the political variety. The latent will of the people finds its ideal expression in the development corporation. In entrepreneurial populism ‘the many’, the people of Khon Kaen, contains within it a sub-set, ‘the few’, whose interests are, nevertheless, assumed to be common interests, and whose role is to activate the latent desire of the many for the betterment of their city. The role of the few is to inspire the many. The affective bonds that bind the few and the many are those of inspiration and belief: the few provide the inspiration and the many are asked ‘to believe’. The biggest challenge, KKTT co-founder Suradech stated in an interview after the LRT decision was made: “people don’t believe (that it will actually happen).” He went on:

We must have resolve. It must be demonstrated and there must be no discouragement. How to make them believe? That’s a very difficult thing. We call it communication (in English): an important thing. Distributing news, article by article. Organising talks and panels on stage, event by event. To go forward or not to go forward. Also keeping people on the edge of their seats. Making people still feel the thrill over whether it will happen.

Suradech 2018

The role of ‘the people’ in entrepreneurial populism is rather limited: their knowledge, their ideas are not sought after, neither is their input in decision-making, only their belief, their enthusiasm is needed. ‘The people’ are conjured as proud residents with an inchoate desire for the betterment of their city which the stimulus of positive news stories translates into support for the corporation’s plans. Entrepreneurial populism consolidates the notion that urban change is a business activity and that business interests are common interests.

The Khon Kaen Model has been celebrated as a pathway to provincial development that eschews Bangkok-centric development. Yet perhaps its most striking feature, and a hallmark of its entrepreneurial urbanism, is the way it promotes the financing of transport infrastructure from private rather than public investment. Far from being presented as a less desirable plan B in the absence of state investment, the use of private finance is regarded by its creators as a key virtue and differentiating principle of the Khon Kaen Model. According to Suradech (2018):

Everyone might say it’s just building a Skytrain, but it’s not just building a Skytrain. The Skytrains that we see in the Bangkok Metropolitan area, Skytrains that are about to appear in the provinces, those Skytrains use tax money from the Thai people. With our Khon Kaen Model our Skytrain does not use subsidy money from the government.

Many of those who shared the interview approved of this endorsement of fiscal restraint, one going so far as to create the unlikely, tax-resistant hashtag #I-Like-That-The-Peoples-Tax-Money-Wasn’t-Used-to-Build-This. It is not difficult to understand this attitude in a country in which public provision by state authorities has been highly circumscribed, and where a highly differentiated and stratified private consumption regime has developed to provide opt outs for those with resources. It is also not unusual in contexts where the state is weak that private corporate actors fill the void and finance, own and operate infrastructures that are public in the limited sense that there are minimal barriers to accessing the services. With the growth of market infrastructure provision around the world it has become increasingly common for private companies, often in varied arrangements with state agencies to claim responsibility for fulfilling public purposes. These responsibilities can form the basis of moral claims made by private sector actors. Horst’s account of the Fijian telecommunications market post-liberalisation focuses on the way global companies, providing goods and services to Fijians, adopt the role of moral actors who bear a responsibility to articulate their obligations to citizen-consumers (Horst 2018, pp. 85-88). The new moral order they create involves casting market interventions, breaking up monopoly and introducing price competition, into a moral discourse. Similarly, the credentials of private sector expertise in the Khon Kaen Model and the identity of the network behind it and its most prominent individuals are established in moral and ethical terms. Private sector involvement is assumed to introduce a higher standard of accountability than that found in local state administration. In May 2018 a public hearing was convened at a central Khon Kaen hotel in response to news that the national Mass Rapid Transit Authority (MRTA) had made a competing bid to build and operate the light rail system. The meeting was an opportunity for members of KKTT, the Khon Kaen mayor and the elected officials of the five municipal sub-districts to restate their case for local ownership and to make a demonstration of public support. One sceptical voice from the floor, representing the Citizens’ Anti-Corruption Network, raised concerns about the potential for corruption in a locally administered project. “The Ministry of Interior is the most corrupt, and the most corrupt part of this ministry are the local administrations. We are taking huge risks allowing the local administration to handle this project instead of MRTA which already has the experience and know-how” (quoted in “Khon Kaen Mayor Defends Light Rail Project”, 2018) In response, the mayor pointed out that the project was not being managed by the local administration, but “professionally run”. As a private-public partnership KKTS would work with “an international auditing firm” (“Khon Kaen Mayor” 2018). It seems that the accounting scandals that have engulfed the big four global auditing corporations have done nothing to damage their superior ethical aura as international businesses in Thailand (Brooks 2018).

The Khon Kaen mayor’s endorsement of KKTS also sought to establish its members’ superior credentials as ‘highly successful, educated, young Khon Kaen people’ and as ‘new generation’ business leaders and administrators. These terms of virtue – new generation, educated – are repeated often in media discourse on the Khon Kaen Model. They are presented as nimble disruptors of a sclerotic bureaucracy. One Khon Kaen resident, a business consultant, approvingly dubbed them hackers. Both ‘young’ and ‘new generation’ are best seen in relative terms, as signifiers that rhetorically establish the distance of those described from a tainted repertoire of provincial politics: kickbacks, single clan dominance – violence. Perhaps the most sociologically rich idealisation of the milieu from which Khon Kaen’s new generation businessmen emerged appeared in an article by Pechladda Pechpakdee.

…the fraternity that characterises Khon Kaen’s “newly wealthy” is remarkable. These new elites are knitted together in networks that revolve around the province and a kind of regional pride…these groups placed faith in regional education standards and resisted the trend of migrating to the capital city. Others pursued higher education in Bangkok or abroad but returned to contribute to the province’s development. A society of Khon Kaen’s elite now partake in a tradition of ‘gathering around the Chinese dinner table’, whereby they take turns each month to host each other over for dinner. These elites repeatedly tell me that they view each other not as ‘rivals in business’ but as ‘friends in business’.

Pechladda 2018

This enthusiastic portrait of a ‘fraternity’ (not a clique, note) of entrepreneurs of Chinese descent deeply committed to the development of their province is at the core of the new moral order that the creators of the Khon Kaen Model seek to establish. Entrepreneurialism fused with localism produces cooperation rather than competition and a deep sense of attachment and responsibility towards Khon Kaen and its people.

Virtuous entrepreneurialism fused with localism can be seen in the self-presentation of the most prominent, media-savvy members of the development corporation. In late 2018 Suradech began to refer to himself on social media as the Akaenger, a vernacularised placemaking play on Marvel’s gang of virtuous caped crusaders (see fig. 3). “Thai people have not yet grasped that public money will not be used to create the light rail system in Khon Kaen”, he wrote on Facebook under a video interview he had given. “Listen carefully”, he added, “the #Akaenger will explain it to you”. When asked who the Akaengers are by a puzzled FB commenter Suradech responded magnanimously with a slice of inclusive entrepreneurial populism: if you are Khon Kaen, you are an Akaenger already. The Akaenger is, of course, a doer, a person of action, and the small army of vocal Facebook supporters of the development corporation and its ‘new generation administrators’ respond to a critical commenter by bemoaning those who do nothing but talk. “The doers put in the capital and money without having to have done so at all. The talkers keep talking and talking. One of the doers is a former boss of mine. I’ve seen it from the beginning. Why does he do it? For what? He really, really, really wants to see Khon Kaen develop!” The critic’s response to this is unfazed in its directness. In a dig at the new gen administrator tag the commenter says: “this job of local politics is something people vie for the seats, isn’t it?”. He then continues,

What I am doing is expressing my views and examining the actions of those in power, according to the rights I deserve as a citizen…. I am not anyone’s fellow clan member, and I don’t have the ambitions to become someone’s fellow clansman. I don’t think that I have to express my views discreetly for the sake of some people…What opinion have you really expressed? Except for saying things to appease sons of millionaires and taking a jab at others.

Facebook post, 3rd November 2018

As this critic suggests, the Akaengers, the new generation administrators, have gained their influence over the shape of local development without having to compete electorally for it. They are a clique, tied by personal friendship networks and common business interests. As the political scientist Michael Nelson writes, the thing about cliques is they “do not have branch offices or regular meetings to discuss politics… Neither would they embark on a publicity campaign to recruit new members. Citizens who want to participate in local or provincial politics cannot ask for a form to apply for membership” (Nelson 2003, 355). In other words, they are inherently socially exclusive, and it is this exclusivity that paradoxically compels the rhetorical conjuring of the people, always united, always coming together, as an existential necessity.

The promise of public things

Paradoxically, perhaps, given the lack of enthusiasm for publicly financed infrastructure provision, the Khon Kaen light rail network has been embraced by some as a public thing, public in the sense that it is a mass-transit infrastructure whose low costs for users imply near-universal accessibility. When the projected 15-baht fare tariff was announced both local and national news outlets remarked on its exceptional affordability, regarding this as a triumph for the private sector-led Khon Kaen Model. Sharing one such positive magazine article on Facebook, a Khon Kaen University academic who acts as an adviser to the development corporation commented: “Feeling united, having faith, trusting, believing and coming together” (ร่วมใจ เชื่อใจ ไว้ใจ มั่นใจ และพร้อมใจ).

Mass transit potentially does more than move commuters efficiently and sustainably around the city. As the Khon Kaen academic’s comment suggests the light rail network potentially taps into what Honig describes as a desire on the part of citizens “to constellate affectively around shared objects in their pre-commodified or non-commodified form” (Honig 2013, 65). Drawing on the object relations psychology of D. W. Winnicott, Honig proposes that we attend to the generative power of things, their capacity to “enchant, alter, interpellate, join, equalise or mobilise us” (Honig 2013, 69). Honig clarifies that, as with Winnicott’s transitional object, it is not the thing in itself that possesses powers of enchantment. Quoting Lauren Berlant she writes the object of desire is not the thing but ‘the cluster of promises magnetised by a thing’ (quoted in Honig 2013, 64). Public things which acquire a degree of durability are epistemological props for a concrete sense of publicness, they bring commonality into focus, they potentially model democratic orientations. A healthy democracy is hard to imagine, Honig suggests, without ample provision of public things. Wolfgang Streeck (2016, 113-138) makes the converse argument, that democratic impoverishment follows the decline of universal public services and the normalisation of consumers with resources opting out which follows their decline. Perhaps then we should welcome the concrete sense of publicness and the democratic affordances which mass transit enables, not to mention the contribution to lower carbon emissions. These arguments would seem to provide a basis for ‘coming together’ in welcoming a provincial mass transit system which is inclusively priced, and which is designed to encourage a shift away from privatised and individualised transit. Perhaps, in the end, it doesn’t matter that public things are financed, managed or owned privately or in a private public partnership, only that they exist. Perhaps this is a case of ‘win-win’. To assess this claim requires looking at the relationship between transit and land use.

What are the implications of a privately financed light rail system for the urban areas in which it is located? Alongside the light rail proposition the Khon Kaen Development Corporation and the municipality have been promoting a planning and development approach referred to as Transit Oriented Development (TOD). The light rail network, they argue, provides an opportunity for Khon Kaen to simultaneously re-develop a number of key sites in close proximity to proposed LRT station areas, creating vibrant, compact, high-density developments enhanced by pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. Transit Oriented Development has been around as a planning concept for several decades but its prominence in global urban development discourse has grown in recent years. Promoted by key development agencies such as the UN and the World Bank, TOD is regarded as a planning intervention that provides a solution to the problems that beset automobile dominated cities: traffic congestion, fossil fuel consumption, air pollution and urban sprawl (see for example Suzuki et al 2013 & 2015). Advocates argue that TOD has the potential to reduce environmental impacts contributing to more sustainable forms of urbanism which enhance the quality of life for residents. Yet, in a more sober analysis based on a survey of actually existing TOD in the United States, Belzer and Autler argue that the positive outcomes – liveable places, less congestion, improved access to vibrant, successful neighbourhoods – which are part of the rhetoric of TOD are often compromised by the “purely financial rationales” underpinning these projects (2002, p. 6). They explain:

Rail systems generally create value for adjacent land, and transit agencies and the Federal Government see large-scale real estate development as a way to ‘capture’ some of that value. While this return is not necessarily sufficient to pay the total cost of rail investment, it represents at least a partial reimbursement to public coffers.

Belzer & Autler 2002, p. 6

Here Belzer and Autler are describing a scenario in which the costs of building the rail network have been largely met through public investment. As they point out, transit agencies have an interest in promoting dense profitable real estate development around transit stations in order to maximise revenue generation. In practice, they argue, the overarching financial rationale shifts the character of actually existing TOD away from mixed use developments and towards more homogenous office and commercial real estate. This is exacerbated by minimal or absent investment for counter-veiling measures supporting affordable housing and minority businesses. How do these concerns about publicly funded transit and TOD translate to a context in which the costs of building the rail network have been met by borrowing from private investors?

According to reports in the Asia Times, of the 15 billion baht cost of building the first phase of the LRT, 4.5 billion would come from the KKTS company with the remaining 10.5 billion coming from foreign investment funds (Janssen 2019). KKTT co-founder Suradech was reported to be talking to three foreign investment trusts in China, Europe and the US. The same report cited an estimate from KKTS that the internal rate of return on the rail operation would be 2 per cent, with an additional 11 per cent return from renting out retail, office and advertising space from land along the route. In a recent interview Kamolpong Sanguantrakul, another KKTT co-founder and current head of the chamber of commerce, stated that to make the TOD sites a success the private sector in Khon Kaen were busy promoting the new development sites to a number of big multinational telecoms companies who were known to be seeking to expand their call centres in the regions (Kamolpong 2019). They were also hoping to lure corporate climate refugees seeking to relocate their operations from flood prone Bangkok. Judging by these statements the dominant vision of what TOD should accomplish in Khon Kaen is governed by the financial imperatives that flow from the LRT financing model, it should maximise revenues in order to provide an attractive rate of return to investors. The risk, as critics of actually existing TOD such as Belzer and Autler highlight, is that revenue maximisation tends to result in homogenous development dominated by office and commercial real estate product, far from the ideal of vibrant, walkable, mixed-use neighbourhoods. As Clarke and Cochrane (2013, p. 14) argue the geographies of localism are never straightforwardly local. The entrepreneurs’ much vaunted attachment to Khon Kaen translates into a development model shaped by the cost-saving rationales of transnational private sector actors. The urban developments created by the financial imperatives of TOD under the Khon Kaen Model are likely to be as local as the phony palm trees that incongruously dot the CGI landscapes of the development corporation’s promo videos.

Looking beyond these instances of TOD-flavoured civic boosterism there appears to be little discussion of what equitable, socially just transit oriented development might look like. Studies have been made assessing the existing physical environment around the proposed LRT station sites whilst evaluating their capacity to attract inward investment. Analysis has been made of TOD in other cities, delegations from the development corporation have been sent on fact-finding missions to Portland, Oregon and Memoranda of Understanding have been signed between the relevant transit authorities. One question remains unasked, what impact will transit-oriented development around the LRT network have on the working poor and the informally housed in Khon Kaen. TOD is a process in which proximity to transit is created as a scarce resource. As Sheller writes: “In any city, there’s a finite supply of real estate with good access to transit, safe and walkable neighbourhoods, and animated, vibrant streetscapes. Invariably, well-off segments of society outbid others for these choice areas displacing long-term residents and the working class” (2018, p. 71) Citing the example of projects in a number of Colombian cities in which large scale affordable housing was built on the back of a Bus Rapid Transit scheme Sheller argues that equitable and socially just transit oriented development is possible but it requires a strategic intervention in real estate markets guided by a commitment to social inclusion. Strategically such an intervention runs counter to conventional understandings of place-making, transit oriented or otherwise.

Media discourse presents the Khon Kaen development corporation as an authentic expression of people power. KKTT symbolically profits from a dualistic conception of power in which there is the state on the one hand – bureaucratic administrative power (centralised, distant, crude and ignorant of local needs) – and citizens on the other. The business leaders behind KKTT are typically discussed in this discourse, not in relation to their business interests as provincial capitalists with complex connections to non-local capital (real estate magnates, franchise holders for transnational corporations, owners of retail empires, food and transport industrialists) but first and foremost in relation to their possession of civic pride and attachment and their sense of responsibility. As local business ‘leaders’ their self-presentation is the antithesis of the popular image of the bureaucrat: they are agile, dynamic, emotionally attached, responsive and responsible. They offer themselves as moral agents, avatars of the engaged citizen, a citizen vanguard, leveraging popular frustration with the failures of the centralised bureaucratic state. It is not only the fact that this self-presentation, the business leader as moral agent securing urban betterment, obscures the actual dynamics of private sector investment in the entrepreneurial city. It is also that the claim to civic agency as a moral virtue claimed by business leaders further diminishes the threadbare infrastructure of local democratic governance. Urban localism in the form of private sector-led initiatives such as KKTT and the Khon Kaen Model rhetorically conjures a people who in actuality have no functional mechanism for securing political representation. As Nelson puts it, unlike a political party nobody can join a business clique by completing a membership form (2002, p. 355). The local trap in the case of the Khon Kaen Model is an anti-political bind that elevates the moral claims to leadership of the local business elite whilst pragmatically embracing the power and agency of the clique. It does so in the absence of a functioning local democracy characterised by a periodic contest for municipal power between political parties. This absence is not only a consequence of the prolonged suspension of local elections, it speaks to the absence of local political parties as organisational forms that offer local citizens differing visions of urban futures, visions that represent competing material and ideological interests. Whatever the development corporation builds in Khon Kaen this political void remains, as does the discontent it produces. The caped crusaders have no solution for this; in fact, they are part of the problem.

Acknowledgements

I am hugely grateful to Peera Songkhünnatham for the many conversations we had during a series of short but intense field trips to Khon Kaen in 2018/19. Many of the ideas developed in this article began to take shape in those dialogues. The research for this article was supported by funding from the Newton Fund: Institutional Links programme (Grant Number: 332437827) and was conducted as part of a project in collaboration with the Centre for Contemporary Social and Cultural Studies at Thammasat University.

References

Ananapibut, Pan. “Tax Reform for a More Equal Society”. In Unequal Thailand: Aspects of Income, Wealth and Power, edited by Pasuk Phongpaichit and Chris Baker. NUS Press: Singapore, 2017.

Askew, Marc. Bangkok: Place, Practice and Representation. London: Routledge, 2002.

Brooks, Richard. “The Financial Scandal No One Is Talking About”. The Guardian, 29 May 2018, sec. News. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/may/29/the-financial-scandal-no-one-is-talking-about-big-four-accountancy-firms.

Belzer, Dena, and Gerald Autler. “Transit Oriented Development: Moving from Rhetoric to Reality”. The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy, 2002.

Chaloemtiarana, Thak. Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2007.

Clarke, Nick, and Allan Cochrane. “Geographies and Politics of Localism: The Localism of the United Kingdom’s Coalition Government”. Political Geography 34 (1 May 2013): 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.03.003.

Harvey, David. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism”. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 71, no. 1 (1989): 3. https://doi.org/10.2307/490503.

Horst, Heather. “Creating Consumer-Citizens: Competition, Tradition and the Moral Order of the Mobile Telecommunications Industry in Fiji”. In The Moral Economy of Mobile Phones: Pacific Islands Perspectives, edited by Robert Foster and Heather Horst. Acton: ANU Press, 2018.

Thanomkitti, Kharun. 2018. “How Can Khon Kaen Build a Sky Train That Charges Only 15 Baht?” A Day, 4thDecember 2018. https://adaymagazine.com/khonkaenmodel/?fbclid=IwAR2eaIiamQOf44Oq1-U-pWimrzteEqfjr71TzIs0Ucb78u6h0-YQUg3m7bc Accessed 20th January 2020

Janssen, Peter. “All Aboard Thailand’s Decentralization Train”. Asia Times. Accessed 15 January 2020. https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/04/article/all-aboard-thailands-decentralization-train/.

“Kamolpong Sanguantrakul, President of the Chamber of Commerce forging business deals for Khon Kaen’s TOD”. Prachachat Business. 16th August 2019. https://www.prachachat.net/local-economy/news-361323

Keyes, Charles. “In Search of Land: Village Formation in the Central Chi River Valley, Northeast Thailand”. Contributions to Asian Studies 9 (1976): 45–63.

Keyes, Charles. “Millenialism, Buddhism and Thai Society”. Journal of Asian Studies 36, no. 2 (1977): 283–302.

Keyes, Charles. Finding their Voice: Northeastern Villagers and the Thai State. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2014.

Hewison, Kevin. “Responding to Economic Crisis: Thailand’s Localism”. In Reforming Thai Politics, edited by Duncan McCargo. Denmark: NIAS Publishing, 2002.

Honig, Bonnie. “The Politics of Public Things: Neoliberalism and the Routine of Privatization”. No Foundations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Law and Justice, 2013, 18.

“Khon Kaen Mayor Defends Light Rail Project Against Meddling from Bangkok”. Isaan Record, 29th May, 2018. https://isaanrecord.com/2018/05/29/khon-kaen-mayor-defends-light-rail-project-against-meddling-from-bangkok

McCargo, Duncan, ed. Reforming Thai Politics. Denmark: NIAS Publishing, 2002.

Nelson, Michael H. “Chachoengsao: Democratizing Local Government?” In Thailand’s Rice Bowl: Perspectives on Agricultural and Social Change in the Chao Phraya Delta, edited by Francoise Molle and Srijantr Thippawal, 345–72. Bangkok: White Lotus, 2003. https://www.academia.edu/2089209/Chachoengsao_Democratizing_Local_Government.

Pechladda Pechpakdee. “The Khon Kaen Model: Eschewing Bangkok-Centric Development”. New Mandala (blog), 22 May 2018. https://www.newmandala.org/khon-kaen-model-eschewing-bangkok-centric-development/.

“The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2017-2021)”. Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board, n.d. http://www.nesdb.go.th/nesdb_en/ewt_w3c/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=4345.

Purcell, Mark. “Urban Democracy and the Local Trap”. Urban Studies 43, no. 11 (2006.): 1921–41.

Sheller, Mimi. Mobility Justice: The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes. London: Verso, 2018.

Skinner, G. William. Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1957.

Songkhünnatham, Peera. “The Khon Kaen Model(s): When Terror and Transportation Infrastructure Meet”. New Mandala (website), 16 January 2019. https://www.newmandala.org/the-khon-kaen-models-when-terror-and-transportation-infrastructure-meet/.

Streeck, Wolfgang. How Will Capitalism End?: Essays on a Failing System. London: Verso, 2016.

Suradech Taweesaengsakulthai, Interview, Esan Biz. 3rd November 2018. Accessed on 15th January 2020 at Esan Biz Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/esanbiz/videos/732567073763322/.

Suzuki, Hiroaki, Roberto Cervero, and Kanako Iuchi. Transforming Cities with Transit: Transit and Land-Use Integration for Sustainable Urban Development. Urban Development Series. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2013.

Suzuki, Hiroaki, Jin Murakami, Yu-Hung Hong, and Beth Tamayose. Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land-Value Capture in Developing Countries. Urban Development Series. Washington DC: World Bank Group, 2015.

Theparat, Chatrudee. “Citizens Taking Initiative in Khon Kaen”. Bangkok Post, 2017, 1st September 2017 edition. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1316747/citizens-taking-initiative-in-khon-kaen.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. Friction. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Wyas. “5 Proposals from Future Forward Party Support Local Government’s Decision-Making Power in Fiscal Affairs”. Voice Online, 14th January 2020. Accessed 7th May 2021.

http://www.voicetv.co.th/read/RQf6pbKH-